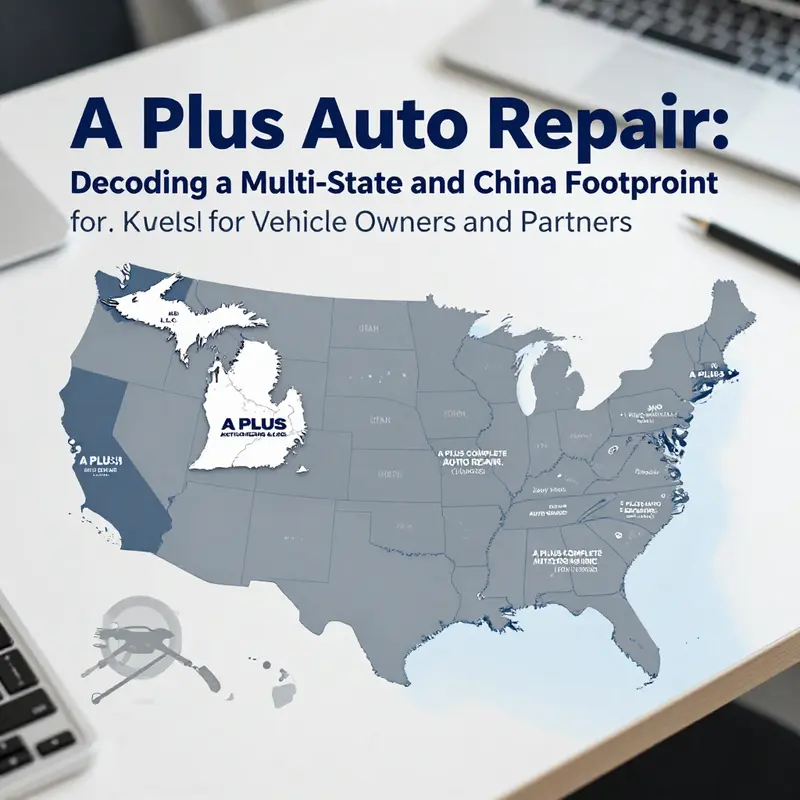

Across the automotive landscape, a single brand name can mask a network of independent businesses. ‘a plus auto repair’ illustrates this reality: six distinct entities, registered in Michigan, Utah, North Dakota, California, New York, and Suzhou, Jiangsu, China, each with its own address and, in some cases, a designated agent. For motorcycle owners, auto owners, auto parts distributors and wholesalers, and repair shops or garages, this arrangement matters. It affects who you collaborate with, which regulatory or safety standards apply, and how records are reported and verified. The result can be a powerful platform for coverage and collaboration—along with a need for careful due diligence to avoid gaps, overlaps, or misaligned expectations. This article examines three tightly linked lenses that illuminate the picture: (1) Corporate footprint across states and China, (2) Service profiles and agency representation that translate governance into everyday operations, and (3) Data integrity, public records, and information gaps that shape trust and decision-making. Each chapter builds on the last, helping readers map practical steps—from verifying registration details to assessing service commitments and asking for primary documentation. By tying together footprint, governance, and record accuracy, the piece offers a practical framework for owners and partners to navigate a multi-entity brand with confidence.

A Patchwork of Service: Tracing A Plus Auto Repair’s U.S. and China Footprint in a Transforming Auto World

Across the map of the automotive service landscape, the name A Plus Auto Repair surfaces in multiple, seemingly parallel threads. What begins as a simple search for a local shop quickly unfolds into a broader story about how independent auto care operates in a era of rapid technological change and global supply dynamics. The information at hand reveals a constellation of entities bearing the A Plus Auto Repair label, clustered in Michigan, Utah, North Dakota, California, New York, and even extending beyond the United States to a location in Jiangsu Province, China. Each entry points to a distinct corporate registration, a separate office or agent, and a unique local market footprint. There is no single corporate monolith here; instead, there is a decentralized network of shops sharing a common naming convention, a shared sense of service, and a common set of pressures—competitive, regulatory, technological, and logistical—that shape how they operate and how customers experience their work. In effect, the A Plus Auto Repair tag becomes a case study in how the aftermarket evolves when competition is thick, consumer expectations rise, and technology introduces new repair challenges with every high-voltage battery and connected vehicle that rolls into a bay. As such, this chapter does not merely catalog locations. It argues that the apparent coincidence of names is both a reflection of entrepreneurial independence and a sign of a broader structural shift in the automotive service ecosystem. The United States, with its sprawling geography and a dense fabric of small and mid-sized repair shops, has always rewarded local trust. APlus-branded shops emerge in this setting as local anchors that offer convenient access to maintenance, diagnostics, and repairs. Yet the global dimension of the footprint—ending in a Chinese address in Jiangsu—highlights how supply chains, training, and market expectations no longer stop at national borders. The same day that a shop in California orders parts, a factory in a neighboring state or a distant supplier can be directing a manufacturing cadence in ways that ripple out to the service bays of Montebello or Brooklyn. The chapter begins with the observable reality of the footprint and moves quickly into why this footprint matters. The U.S. auto market is segmented into thousands of service locations, each competing for the same finite pool of vehicle owners who demand reliability, speed, price transparency, and a good repair experience. In this environment, a name like A Plus Auto Repair can function as a local brand cue—an implicit promise of basic competence and a standard of care. But when that name appears across multiple states, consumers face questions: Are these shops part of the same organization? Do they share the same quality standards, the same training, the same network of suppliers? Do they, in effect, behave as one chain, or do they operate as independent operators who just happen to choose a similar name to signal their craft? The data points toward independence wrapped in a familiar label. A closer look at each listed entity reveals a mosaic of jurisdictions and regulatory environments. In Michigan, the A-PLUS TIRES & AUTO REPAIR, L.L.C. nods to a regional ecosystem of tire services and light mechanical work, common in states where tire shops often double as repairers and part-supply hubs. In Utah, A PLUS AUTO REPAIR sits at 916 E St George Blvd in St. George, a community with a mix of family-owned auto shops and newer enterprises that aim to capture a tourist and resident mix. The registered agent and address in Washington, Utah, suggest a common practice in which small businesses cover themselves with local representatives who can manage filings and service proxies, a practical approach when ownership structures can be as fluid as the local road network. North Dakota contributes another layer, with A PLUS AUTO REPAIR INC registering in Bismarck and listing a physical address at 3604 Global Dr, near the industrial corridors that support fleets, big-box retailers, and maintenance facilities. A local agent—a named individual—further anchors this presence, a reminder that in many states the repair trade is a people business as much as a machine business. California adds yet another dimension with A PLUS AUTO REPAIR INC at 107 Van Norman Rd in Montebello, where the interplay between warranty work, part sourcing, and regulatory compliance creates a demanding operating environment. Brooklyn, New York, hosts A PLUS AUTO REPAIR SERVICE INC at 533 Remsen Avenue, a district known for dense population and a high demand for dependable maintenance and quick-turnaround service. The occasional Chinese entry—A PLUS COMPLETE AUTO REPAIR INC. at a Jiangsu address in Suzhou—further highlights how a name that is both generic and straightforward can migrate across borders as the global auto world grows more interconnected. All these pieces together form a footprint that looks, on the map, like a scattered constellation rather than a single, tightly controlled network. Yet in practice, the real effect is more nuanced. These shops share an operational culture: a vocational identity rooted in hands-on repair work, a customer-first orientation, and a responsiveness to the local traffic of vehicles needing routine maintenance, diagnostic checks, and occasional hard-to-diagnose failures. The landscape around them, however, is changing at an accelerating pace. Electrification introduces new failure modes, battery safety considerations, high-voltage systems, and software-driven diagnostics that demand different training, tools, and supplier ecosystems compared with traditional internal-combustion engine maintenance. A shop that can confidently diagnose a misfire or a cooling system leak in a gasoline vehicle may be caught flat-footed when confronted with a battery pack fault, a thermal management issue, or a software update that requires secure access to vehicle networks. The result is a demand for continuous learning, not only for technicians but also for shop managers who must balance warranty requirements, parts availability, and customer expectations in a market where technology cycles are increasingly rapid. The international dimension intensifies the need for cross-border knowledge and resource sharing. Even as the U.S. repair market remains large and fragmented, the global automotive supply and production model continues to evolve. A major Chinese NEV manufacturer has been expanding internationally, aiming to position its vehicles in more markets and rental fleets, and to diversify the supply chain with regional production and local assembly or assembly-adjacent components. While the details of that manufacturer’s global footprint are not the content of this chapter, the consequences are clear: a broader range of electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles on the road means a growing aftermarket segment focused on high-voltage safety, battery maintenance, thermal management, and software updates. For repair shops, this means new training partners, new diagnostic equipment, and a new baseline for what constitutes a complete service offering. The aftermarket is not simply about changing oil and rotating tires anymore. It is about interpreting a vehicle’s data stream, identifying anomalies in battery temperature management, understanding battery conditioning cycles, and communicating the significance of software-driven fault codes to customers who expect fast, clear explanations and fair pricing. In this sense, the A Plus Auto Repair footprint becomes illustrative of a broader dynamic: a dispersed network of small and mid-size operators who know their local markets intimately but must increasingly connect with a nationwide and even international knowledge economy for parts sourcing, tool access, and standardized service practices. This is where the concept of an ecosystem, rather than a chain, begins to emerge. An ecosystem implies shared norms, common training modules, and a mutual interest in upholding a recognizable standard of care, even though corporate ownership may differ across locations. The practical implications for customers are nuanced. Some will value the convenience of a familiar brand name across multiple cities, particularly when traveling or relocating. Others will prioritize the ability to ask a question of a shop that has a track record in their community and can offer a warranty that aligns with local expectations. In either case, trust emerges not solely from a brand promise but from a lived experience: the courtesy with which intake is conducted, the clarity of the diagnostic process, the transparency of pricing, and the technician’s ability to translate complex mechanical and electrical issues into accessible explanations. The intersection of local trust and global knowledge creates a fertile ground for delivering higher service quality. Shops that invest in consistent diagnostic protocols, provide ongoing technician training, and establish transparent parts sourcing can differentiate themselves from the crowded field. The broader supply-chain context reinforces this point. Parts availability now travels through a web of manufacturers, distributors, and regional warehouses that are sensitive to geopolitical shifts, tariff regimes, and the ebb and flow of demand from different sectors, including fleet maintenance and consumer repair. A small shop in Utah might source a thermostat from a regional distributor while a counterpart in California relies on a nearby warehouse for a battery module. When a policy change or a global event disrupts supply lines, these shops can feel the impact almost immediately through longer wait times, higher prices, or backorder issues. The awareness that supply-chain dynamics can ripple through a neighborhood repair shop adds a layer of strategic importance to the training and equipment decisions a shop makes. It also elevates the role of shop management in engaging with suppliers, negotiating terms, and maintaining a balanced inventory that supports both routine maintenance and more complex diagnostic work. In this light, the A Plus Auto Repair footprint serves as a mirror for the larger aftermarket economy: a mosaic of small businesses that must, simultaneously, preserve local accessibility and participate in the global value chain that underpins modern vehicle technology. The chapter’s reference to the Chinese NEV landscape, and to the broader narrative of China’s growing influence in the auto industry, underscores a practical reality for U.S.-based repair shops: the need for specialized capabilities that were previously niche and are now becoming standard. The so-called China plus one strategy—manufacturing diversification beyond a single hub—feeds into this. If suppliers and manufacturers diversify their production and distribution networks to include Southeast Asia and other regions, repair shops gain access to a broader palette of parts and components, but they also face new compatibility standards, faster refresh cycles, and the challenge of keeping up with ever-evolving vehicle architectures. This is not merely a supply problem. It is also a customer expectations problem. Consumers who purchase or lease more technologically advanced vehicles expect efficient maintenance experiences, real-time communication about service status, and access to preventive care programs designed to extend vehicle life and optimize total cost of ownership. The A Plus Auto Repair narrative, with its multiple independent operators, reveals how these expectations travel with customers as they move between states or across borders. A customer who knows one A Plus location may reasonably expect similar service quality from another location bearing the same name, even if the operations are not tightly integrated. It’s a delicate balance: local autonomy can foster entrepreneurship, speed, and tailoring to local markets; standardized training and quality assurance can protect the customer experience as vehicles become more complex. In practice, the best-performing shops in this milieu will be those that combine strong local service with access to shared knowledge and a transparent, data-driven approach to maintenance. They will invest in diagnostic tools capable of reading high-voltage systems and vehicle networks, embrace secure data handling for software updates, and partner with reputable training programs that keep pace with industry shifts. This is where the digital layer matters as much as the mechanical layer. Vehicle health data, service histories, and diagnostic outcomes can be captured, stored, and compared across locations, enabling a learning loop that benefits customers wherever they live. For a customer, the result is a more predictable repair experience, fewer repeat visits, and a clearer view of the maintenance path that keeps a vehicle on the road longer. For the shops themselves, there is an opportunity to convert unfamiliar customers into repeat clients by delivering a consistently reliable, transparent, and education-forward service journey. The informational density in the broader global automotive environment means shop operators must act not only as technicians but as caretakers of a broader ecosystem that includes suppliers, insurers, lenders, and fleets. The existence of a multi-location naming convention with a geographic spread throws into relief the need for clear branding that communicates competence without implying corporate homogeneity. It also invites regulators and industry observers to consider how the aftermarket is adapting to a world where parts specifications and repair protocols are increasingly standardized—yet ownership structures remain diverse. One practical implication is the growing importance of credentialing, both for technicians and for shop managers. Certification programs, standardized repair procedures, and a shared lexicon for diagnostic codes become the currency of trust in a dispersed network. In such a context, even independent operators can co-create a credible regional or national service standard by participating in industry associations, investing in joint training, and adopting common tools and data platforms. The chapter’s closing reflections circle back to the core question: what does it mean for a name—A Plus Auto Repair—to appear in multiple states and a far-off province? It signals entrepreneurial energy and customer accessibility. It also signals a need for vigilance in quality control, for thoughtful investment in advanced training, and for proactive collaboration across locations to ensure service excellence. It hints at a future where repair shops absorb more of the vehicle’s complexity, not fewer, and where the customer experience is defined by clear communication, reliable turnaround, and a consistent level of workmanship regardless of where one seeks service. In a world where the automotive industry is being reshaped by electrification, software, and cross-border supply dynamics, the A Plus Auto Repair footprint stands as a microcosm of how local businesses can persist and adapt. The path ahead will require continuous learning, strategic supplier relationships, and a willingness to embrace technologies that help technicians interpret a vehicle’s digital heartbeat. It will reward shops that translate those capabilities into transparent, customer-centered service. And it will reward customers who seek out repair experiences that combine the convenience of a familiar neighborhood shop with the confidence that comes from professional, well-trained technicians who can manage the complexities of modern mobility. For readers exploring the broader implications of this chapter, a related perspective on the global credit and trade environment shaping the automotive sector offers useful context. See the external analysis from a leading ratings and research firm for deeper insight into how macro dynamics interact with the automotive aftermarket. The ongoing evolution of the industry suggests that the A Plus Auto Repair footprint is less about a single corporate strategy and more about a distributed capability—an ability for independent shops to stay competitive, informed, and connected in a world where a vehicle’s life cycle now spans continents as well as miles. To connect with a broader thread on repair philosophy and the evolving skill set, readers can explore a practical overview of auto repair fundamentals here: A-to-Z Auto Repair.

External context and further reading on the global credit and trade environment affecting the automotive sector can be found here: https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/.

Across States and Profiles: The Service Identities and Agency Ties of A Plus Auto Repair

A Plus Auto Repair presents itself in the research as more than a single storefront or a single corporate banner. Instead, the materials sketch a constellation of independent entities that share a brand name, a common service promise, and a set of operational innovations designed to meet local needs while tapping into national and even international networks. This chapter weaves together the service profiles and the agency representations of these varied shops, showing how the name operates as a practical identity across different legal forms, regulatory environments, and customer expectations. It is a portrait of modern auto repair as both a local craft and a distributed, digitally enabled service system, where branding, trust, and capability must be legible to customers who expect consistent quality even when they travel or move between states and countries.

What the gathered records reveal is a pattern of regional autonomy wrapped in a shared branding rubric. In Michigan, the listing for A-PLUS TIRES & AUTO REPAIR, L.L.C. signals a presence that is registered locally and linked to the broader A Plus ecosystem, even if the exact physical address remains unstated in one primary source. In Utah, A PLUS AUTO REPAIR operates from 916 E St George Blvd in St George, with a registered agent at a separate Utah address in Washington. North Dakota adds another layer with A PLUS AUTO REPAIR INC, anchored in Bismarck at 3604 Global Dr, and the agency representation handled through Craig Geffre at a parallel address. The California node, A PLUS AUTO REPAIR INC, radiates from Montebello at 107 Van Norman Rd, with Walt Yousefian named as the agent. New York contributes A PLUS AUTO REPAIR SERVICE INC, based in Brooklyn, New York, at 533 Remsen Avenue. Finally, the Chinese entry, A PLUS COMPLETE AUTO REPAIR INC., situates itself in Jiangsu Province, Suzhou, within the industrial zone of Huizhi Street, an entry that expands the geographical texture of the name beyond the American market.

The diversity of locations is not accidental. It reflects a broader industry pattern in which a recognizable name or brand can stretch across state lines, while each legal entity adheres to its own regulatory architecture. The US states require registered agents, local business licenses, and appropriate corporate form. In North Dakota and California, for example, the presence of a registered agent—Craig Geffre in Bismarck and Walt Yousefian in Montebello—highlights a core legal reality: corporations must maintain a point of contact for service of process and compliance. This arrangement ensures that customers who encounter the A Plus label in different jurisdictions can expect a baseline of accountability, even as each shop tailors its operations to local market conditions, workforce availability, and regulatory practice. The juxtaposition of a Chinese address with several American registrations underscores a deeper theme: branding in the auto repair sector is increasingly global, yet service delivery remains deeply anchored in local competencies and community trust.

The core service profiles carried by these shops converge onto a familiar map of capabilities. Across the board, A Plus Auto Repair shops position themselves as full-service automotive service providers, skilled at diagnosing and remedying mechanical issues while maintaining vehicles through preventive maintenance. The described competencies—engine diagnostics, brake repair, transmission servicing, electrical system troubleshooting, and routine maintenance like oil changes and tire rotations—form a cohesive portfolio. In practical terms, a customer presenting a modern vehicle can expect a diagnostic process that starts with a structured intake, followed by a systematic test plan using calibrated equipment. The diagnostic phase identifies not only the immediate fault but also potential contributing factors, which informs a repair sequence designed to restore reliability and performance while minimizing the risk of recurrence.

Behind the scenes, technicians in these shops operate within a culture of standards and craftsmanship. The emphasis on certified technicians and advanced diagnostic tools signals a commitment to accuracy and safety. In a field where a misdiagnosis can cascade into further damage or expensive repairs, the reliability of the diagnostic step becomes a customer’s first confidence note. The service profile then transitions to repairs that align with established industry practices and the shop’s own procedural playbooks. Whether replacing a worn brake system, addressing an electrical gremlin, or reconditioning a stranded transmission component, the aim is to return the vehicle to a state that preserves performance, efficiency, and safety. The narrative in the chapter thus frames A Plus Auto Repair not merely as a shop that fixes cars, but as a partner in prolonged vehicle life, where informed maintenance decisions contribute to predictable ownership costs.

The operational sophistication behind these profiles is magnified by how the shops connect with customers and coordinate service delivery. Digital scheduling, streamlined booking processes, and integration with service platforms emerge as a salient feature of the A Plus approach. A notable point in the chapter’s materials is the explicit partnership with Tabby, described as a platform that enhances scheduling flexibility, booking efficiency, and digital integration for customers seeking vehicle servicing. This association signals a broader industry shift: repair shops increasingly rely on fintech-enabled payment and scheduling ecosystems to reduce friction, extend service hours, and expand access to customers who may juggle busy lives and irregular work schedules. Even when the precise business arrangement spans a geographic and corporate divide, the customer experience begins with a clear, convenient interface and ends with transparent pricing and dependable workmanship.

Such digital and operational synergies are not merely conveniences. They reflect a strategic alignment between local service capability and scalable customer access. The Tabby partnership—represented in the chapter as linking A Plus Auto Repair with a technology-enabled booking and payment pathway—illustrates how a shop’s agency representation can extend beyond the formal registrar and into the realm of customer experience design. Agency representation here takes on a dual texture: the legal function of appointing a registered agent or an entity’s formal governance and the business function of partnering with platforms that shape how customers interact with the shop. The legal agents—Geffre in North Dakota and Yousefian in California—anchor the shops in their respective communities, while platform partnerships anchor the same shops to a broader, digitally enabled service ecosystem. In this sense, agency representation becomes a continuum that weaves legal accountability with service accessibility and customer satisfaction.

The chapter also invites readers to consider the branding implications of operating under a shared name in separate jurisdictions. A Plus Auto Repair, in this configuration, resembles a family business more than a traditional franchise. Each shop holds its own corporate identity, with localized address data and agent representation, yet the shared name conveys a promise: expertise, reliability, and a consistent approach to vehicle care. The tension between local autonomy and brand cohesion is manageable when customers perceive a consistent level of professionalism and transparency. The ability to deliver consistent workmanship hinges not only on the technicians’ skills but also on the reliability of the service processes—appointment scheduling, diagnostic reporting, repair sequencing, parts sourcing, and aftercare. A cohesive service profile across shops helps customers build trust across state lines, enabling them to rely on the A Plus name when they move, commute, or travel for business.

In this context, an internal cross-pollination of knowledge and practice becomes a natural byproduct of a distributed brand. When a technician in Utah encounters a vehicle issue similar to one seen in California, the diagnostic minutiae and repair decision trees can be shared, refined, and documented within a common knowledge framework. This reduces guesswork and accelerates problem resolution, especially for customers who own multi-vehicle households or fleet assets that may require service across multiple locations. The idea of a value chain emerges clearly: local intake and front-desk service align with regional workshops that share diagnostic standards, maintenance schedules, and warranty criteria, all tethered by a modern service platform that can route information, schedule follow-ups, and flag maintenance needs. The net effect is a more coherent customer journey, one in which the distance between storefronts feels shorter because the service logic travels with the customer through digital channels and through the alignment of internal processes.

A further layer of depth comes from recognizing how the shops’ profiles address the realities of a diversifying vehicle fleet. Modern vehicles bring complex electrical systems, ecologically minded maintenance considerations, and increasingly sophisticated onboard diagnostics. Shops that emphasize electrical troubleshooting and engine diagnostics convey a readiness to handle future-proof labor—work that anticipates evolving vehicle architectures, alternative powertrains, and high-tech sensor ecosystems. This orientation is particularly meaningful when considered alongside the brand’s geographic spread. A shop in a dense urban borough may see different fault patterns and driving conditions compared with a shop operating in a more spread-out, suburban or regional setting. The shared service philosophy—rooted in methodical diagnostics, ethical customer communication, and transparent pricing—remains the thread that holds the brand together, even as the specifics of daily operations adapt to local demands.

The chapter’s evidence also invites customers to engage in a practical practice when evaluating any A Plus shop: examine the local entity’s public details, confirm the registered agent and business address, and inquire about the shop’s warranty and maintenance policies. The presence of multiple entities with the same brand can be a boon for accessibility, but it also necessitates due diligence. The customer benefits when a regionally anchored agent—an identifiable point of contact for compliance and accountability—stands behind the work. At the same time, the adoption of digital tools and platform partnerships helps ensure consistency in scheduling, in the clarity of quotes, and in the ease of post-service follow-up. In short, the A Plus Auto Repair landscape, as depicted by the chapter, exemplifies a modern hybrid—where local, hands-on craftsmanship meets global branding and digital-enabled service delivery.

For readers who want a broader map of how service profiles are presented across shops, a general guide offers a useful frame of reference. The A-to-Z Auto Repair resource provides a concise overview of the spectrum of services, the typical customer journey, and the ways shops structure their maintenance programs. It can help readers understand where A Plus Auto Repair’s profiles sit within the wider industry landscape, offering a comparator against which to gauge the quality and clarity of a shop’s public facing materials. See more at A-to-Z Auto Repair.

As we close this look at Chapter 2, the central takeaway centers on how service profiles and agency representation shape the customer experience and the business’s resilience. The shops’ service portfolios offer robust, practical care for today’s vehicles, underpinned by skilled personnel and reliable diagnostic processes. The agency dimension—encompassing legal agents and strategic platform partnerships—ensures that the brand’s footprint is legible and trustworthy across jurisdictions while enabling scalable, customer-centric operations. The result is a nuanced example of how a common name can function as a credible, locally rooted service identity across a distributed network. It also suggests a path forward for customers and researchers alike: when evaluating a repair provider, look beyond a single storefront and examine how the brand’s local entities—through their agents, addresses, and platform integrations—together deliver a consistent promise of quality, transparency, and convenience.

External resource for further reading: LinkedIn company profile of the brand highlights the corporate presence and public-facing identity that underpins these regional shops. https://www.linkedin.com/company/a-plus-auto-repair-inc/

Chapter 3: The Data Mosaic Behind A Plus Auto Repair — Public Records, Multi-State Footprints, and the Gaps in a Car’s History

The story of A Plus Auto Repair starts with the simple premise that a vehicle’s health is only as trustworthy as the records that describe it. When a shop operates across state lines and even across national borders, the echoes of a single service event can fracture into a mosaic of fragments. In the public eye this is more than a bookkeeping puzzle; it is a matter of trust, safety, and the future reliability of diagnostics and repairs. The dataset of A Plus Auto Repair illustrates how, in a landscape where many independent entities share a brand name, data integrity becomes the fulcrum on which customer confidence teeters. Multiple entries—ranging from A-PLUS TIRES & AUTO REPAIR, L.L.C. in Michigan to A PLUS AUTO REPAIR INC in North Dakota, to an A PLUS AUTO REPAIR SERVICE INC in New York, and even an A PLUS COMPLETE AUTO REPAIR INC in Jiangsu—show how a common nomenclature can mask divergent records. In practical terms, a consumer who visits one shop for a brake job may later rely on another location for a diagnostic, and without a synchronized, verifiable history, the lineage of service events can drift apart. This drift is not merely an academic concern. It translates into potential misdiagnoses, inconsistent warranties, and a chilling erosion of trust when a customer discovers that the service history on a vehicle does not align with the official records maintained by the company or by the local regulatory databases.

In the modern auto-repair ecosystem, the tension between fieldwork and centralized data is all too real. Technicians often begin with handheld diagnostic tools at the vehicle, assessing fault codes, observing wear patterns, and recording notes in local devices. When the fieldwork concludes, the technician must reconcile those notes with a master information store that seeks to reflect every repair, maintenance task, part replacement, and diagnostic result in a single, authoritative ledger. The problem is not only that handheld devices can operate in disconnected modes but also that the authorization and synchronization flows are uneven. If a technician can alter a field device without ensuring a complete and timely reflection of that change in the central repository, the system’s integrity begins to fray. The risk is especially pronounced in a distributed, multi-entity environment where a single brand name hides distinct corporate legal entities, each with its own license, management, and data governance practices.

Consider the public records surrounding A Plus Auto Repair entities. Public databases contain thousands of profiles that establish legitimacy, operating status, and basic identifiers. These profiles, when juxtaposed with the internal histories maintained by individual shops, reveal the potential for misalignment. The public record ecosystem—comprising registration details, addresses, agent information, and industry classifications—acts as a check against the internal ledger. But it can also expose gaps when the internal system assumes a central identity that does not match the scattered, state-regulated footprints visible in the public domain. The consequence is not only a potential mismatch in addresses or ownership details; it is the more insidious risk that the service history of a vehicle could be inferred differently by the customer, the shop, and the regulator.

Bridging this divide requires more than routine synchronization; it requires a disciplined method for detecting and repairing inconsistencies that arise when data flows from disparate sources. A conceptual approach, drawn from the broader field of data management, relies on exploiting functional dependencies—constraints that relate certain attributes to others in a way that should always hold true. In the automotive repairs lifecycle, functional dependencies might include the idea that a service event tied to a particular vehicle VIN should correspond to a specific service date, a documented technician, a consistent mechanic’s note, and the parts used in that service. When a field report deviates from these expectations—perhaps because a diagnostic result is recorded on a handheld device but not reflected in the central record, or because a part number appears inconsistent across multiple sources—the system flags an anomaly.

The challenge, of course, is that source reliability is seldom known a priori. Different shops, different state registries, and different software stacks all carry varying degrees of accuracy. An iterative framework can be employed to address this uncertainty. In such a framework, the process alternates between repairing data and refining estimates of source reliability. Initially, the system treats each source as a candidate with all possibilities open, then it identifies violations of the functional dependencies across multi-source data. Each detected violation serves as evidence about the reliability of the sources involved. As the iterations proceed, the system increases confidence in the more reliable sources and uses that confidence to guide subsequent repairs. The outcome is a cleaner, more coherent history of a vehicle’s service events, where discrepancies are progressively reconciled and the most trustworthy narratives are elevated to the official record. This is not a theoretical luxury; it is a practical necessity in distributed networks where customers expect consistent service histories and where regulators demand traceable governance of business operations.

In practice, applying a reliability-aware repair framework to A Plus Auto Repair’s multi-entity footprint would mean systematically aligning service events, diagnostics, and parts data across all operating locations. It would also mean reconciling the social and legal identities behind those entities. The Michigan entity, the Utah location, the North Dakota office, the California facility, and the New York service shop each contribute to a composite record that should, ideally, tell a single, coherent story about a given vehicle. When record-keeping practices diverge—such as differences in retention periods, data schemas, or consent and privacy constraints—the iterative repair process must be capable of adjusting both the data and the estimated reliability of the stemming sources. Over time, this yields a more robust data graph in which field modifications, when properly synchronized, can be validated against the central ledger, reducing the risk of data drift and the misalignment of service histories.

The empirical promise of such approaches is not merely theoretical. Studies that implement iterative, dependence-based repairs across multi-source datasets demonstrate superior accuracy in truth discovery and data repair compared to more static or rule-based methods. In the automotive repair context, this translates into more accurate service histories, better maintenance diagnostics, and a higher likelihood that a customer’s documented experiences align with what the central system records. It also underpins more reliable warranty adjudications, consistent preventive maintenance recommendations, and a more trustworthy relationship between customers and repair providers. No single shop can claim to be immune from data gaps. What matters is the system-level capability to detect, quantify, and progressively close those gaps through an integrated data governance discipline that respects the realities of field work, regulatory oversight, and customer expectations.

Public records, in this frame, function as both a mirror and a map. They reflect the identity of a business as registered, licensed, and recognized by local authorities, and they map out the broader ecosystem in which that business operates. For customers, the public profile of a repair entity offers a degree of transparency and accountability. It helps answer essential questions: Is this shop legitimately registered? What is its legal form and ownership? Where is it located, and whom can I contact for official records or audits? These questions are not merely bureaucratic; they are necessary for building confidence that the repair ecosystem is coherent and that service histories can be trusted. For businesses, the public record is a beacon for due diligence. When a potential partner or customer conducts a cross-check, the alignment—or misalignment—between public data and internal service histories becomes a signal that invites deeper investigation.

The public-record ecosystem also helps illustrate how data integrity challenges arise. When a shop’s legal name, address, or agent information shifts across time, the corresponding internal history must reflect those changes in a way that preserves the continuity of service. If a shop rebrands or transfers ownership, the central ledger must encode this transition without breaking the chain of prevous service events. The risk is an orphaned entry, a service record that cannot be confidently tied to a vehicle’s true history, or a mismatch in warranty claims tied to the wrong corporate identity. The reality is that many business profiles exist, sometimes overlapping in confusing ways. The existence of more than one A Plus Auto Repair entity across states underscores the need for a robust cross-referencing mechanism that can align the internal narratives with the public profiles, while preserving the historical integrity of each entity’s records.

A practical way to ground these ideas is to consider how a vehicle’s diagnostic journey travels from the field to the central repository. A technician on the shop floor reads fault codes, logs observations, and annotates the work performed. That signal then travels through the shop’s data pipeline and must eventually land in a central knowledge base that is accessible to service writers, service managers, and customers through portals or invoices. If the central repository accepts the field notes without validation, or if it fails to reconcile a recommended service with the actual parts used, the data integrity of the entire repair history can deteriorate. This is where the iterative, reliability-aware repair framework proves its worth. By explicitly modeling the likelihood that a given field entry is accurate, and by cross-checking that field entry against other credible sources—e.g., procurement records, parts inventories, vehicle VIN histories—the system can decide when to merge, correct, or even suppress conflicting entries. The result is not simply a tidy database; it is a trusted narrative that can be traced, audited, and trusted by the customer and by regulators.

To connect these ideas back to the broader literature, public records and automated data repair methodologies together form a powerful toolkit for closing information gaps. The public records provide the scaffolding—a checked, verifiable identity and a traceable lineage of business activity. The automated repair approaches provide the muscles—the capability to detect inconsistencies, measure source reliability, and repair data in a way that improves over time. The interplay between these two strands—public transparency and automated integrity reinforcement—offers a pathway to a more reliable automotive repair ecosystem. In this vision, a consumer who visits multiple A Plus Auto Repair locations experiences a consistent, coherent service history. The technician who looks at the vehicle’s past maintenance sees a record that has been carefully stitched together from field notes, central logs, and public records. The manager who must respond to a warranty claim or to an audit sees a narrative that can be traced back through every step of the repair journey. In short, data integrity becomes the quiet infrastructure of trust that makes the practical work of auto repair meaningful to customers, regulators, and business owners alike.

Public records are not merely passive repositories; they are active participants in the reliability ecosystem. They help ensure that the operations of a dispersed network of shops remain legible to stakeholders who do not inhabit the inner circle of day-to-day repair activity. They enable cross-location accountability by providing a shared vocabulary and a reference frame for identifying where an identical entity diverges into separate legal identities. They also reveal information gaps—moments when a service event is documented in a local log but not echoed in the public record or in the central ledger. The existence of such gaps is not a verdict on a shop’s integrity; it is a diagnostic signal that the data governance architecture needs strengthening. Addressing these gaps requires not only technical fixes but also organizational discipline: clear data ownership, standardized data capture, and a policy for timely, deterministic synchronization across all channels and all locations.

Among the sources that illustrate the breadth of this landscape is the broader body of research on automated data repair. A notable strand of work demonstrates how exploiting functional dependencies in concert with iterative reliability estimation can outperform traditional rule-based approaches. This research, conducted on synthetic and real-world datasets, shows that the repairs are not merely cosmetic: they reconstitute a more faithful representation of events across multiple sources. The automotive domain benefits from these insights because service histories are inherently multi-source: field notes from technicians, parts usage logs, vehicle history reports, and public business records all contribute strands to a single truth. When these strands are semantically aligned through dependency-aware repair, the resulting data becomes a more trustworthy substrate for diagnostics, scheduling, and accountability.

The practical takeaway for a multi-location brand like A Plus Auto Repair is straightforward, even if the implementation is complex. Build a data governance architecture that treats the public record as a core reference and the internal records as evolving proofs that must be reconciled continually. Invest in processes that ensure synchronization after every field interaction. Create audit trails that demonstrate how field modifications propagate through the central store. Train technicians and service writers to annotate notes with consistent taxonomies and standardized fields. And, above all, design the system so that it can learn from each repair cycle what constitutes a reliable source, how to weigh conflicting evidence, and how to repair inconsistencies without erasing meaningful history.

For readers who want a practical, industry-facing lens on this topic, consider the way a well-documented repair journey could be enriched by a curated example from the field. The public record ecosystem supports this by enabling cross-verification with the identity and location of the business, while the internal systems carry the rich, nuanced detail of each service event. The integration of these layers creates a resilient narrative about a vehicle’s life—a narrative that both customer and technician can trust. It is through this trust, built on robust data integrity practices, that a dispersed network of auto-repair shops can sustain a durable reputation. It is through this integrity, rather than flashy marketing alone, that the idea of a brand—such as A Plus Auto Repair—transcends the sum of its locations and becomes a coherent, reliable promise to customers across communities.

For readers seeking further insight into how data integrity concepts translate into practical business guidance, a helpful reference is available in the broader research community. The external resource, which outlines the effectiveness of a functional-dependency-based repair framework in cross-source data environments, provides a rigorous foundation for the claims discussed here. It demonstrates, in controlled experiments, how iterative reliability estimation guides both repair and source reputation refinement, yielding improvements in data fidelity that persist across varied data landscapes. This work reinforces the idea that maintaining a trustworthy service history is not a one-off data cleanup task but a continuous, adaptive process that aligns technological safeguards with the realities of field work and public oversight.

As a final note, the journey from field notes to public records and back again is not merely a technical choreography. It is a human-centered pursuit of accountability, transparency, and care for customers who entrust their vehicles to a network of shops. Data integrity, public records, and information gaps are not abstract concepts reserved for data scientists; they are the daily realities of maintaining a repair ecosystem where misalignment can have real-world consequences. By embracing an iterative, dependency-aware approach to data repair and by treating public records as both a clarifying lens and a verification beacon, the automotive repair community can move toward a future where every service event is anchored in a coherent, traceable, and trusted history. The result is a more reliable, more customer-centric industry—one that respects the complexity of multi-entity operation while delivering consistency, clarity, and confidence to every driver who depends on it.

External resource: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030645732500087X

Internal reference for practice: A to Z Auto Repair

Final thoughts

Understanding the ‘a plus auto repair’ landscape empowers readers to engage more confidently with automotive partners. The footprint across states and China reveals both reach and the need for verification. The service profiles and agency representation illustrate governance in practice, not merely promises on a business card. The data integrity discussion underscores that records can lag or diverge between jurisdictions, so due diligence, cross-checking filings, and requesting primary documents are prudent steps. For motorcycle owners, auto owners, auto parts distributors, and auto repair shops, the core message is to treat the brand as a family of legitimate local entities rather than a single monolith. Verify registration details, confirm the actual operating entity and its agent, request service-level commitments, and maintain clear lines of communication. By approaching with curiosity and a readiness to verify, stakeholders reduce risk and unlock smoother collaboration, better parts sourcing, and safer vehicle maintenance. The takeaway: navigate a multi-entity brand by identifying exactly which entity you are dealing with, where it operates, and how it governs service.